Penmachine

23 April 2010

What Darwin didn't get wrong

Last October I reviewed three books about evolution: Neil Shubin's Your Inner Fish, Jerry Coyne's Why Evolution is True, and Richard Dawkins's The Greatest Show on Earth: The Evidence for Evolution. It was a long review, but pretty good, I think.

There's another long multi-book review just published too. This one's written by the above-mentioned Jerry Coyne (who will be in Vancouver for a talk on fruit flies this weekend), and it covers both Dawkins's book and a newer one, What Darwin Got Wrong, by Jerry Fodor and Massimo Piattelli-Palmarini, which has been getting some press.

Darwin got a lot of things wrong, of course. There were a lot of things he didn't know, and couldn't know, about Earth and life on it—how old the planet actually is (4.6 billion years), that the continents move, that genes exist and are made of DNA, the very existence of radioactivity or of the huge varieties of fossils discovered since the mid-19th century.

It took decades to confirm, but Darwin was fundamentally right about evolution by natural selection. Yet that's where Fodor and Piattellii-Palmarini think he was wrong. Dawkins (and Coyne) disagree, siding with Darwin—as well as almost all the biologists working today or over at least the past 80 years (though apparently not Piattellii-Palmarini).

I'd encourage you to read the whole review at The Nation, but to sum up Coyne's (and others') analysis of What Darwin Got Wrong, Fodor (a philosopher) and Piattelli-Palmarini (a molecular biologist and cognitive scientist) seem to base their argument on, of all things, word games. They don't offer religious or contrary scientific arguments, nor do they dispute that evolution happens, just that natural selection, as an idea, is somehow a logical fallacy.

Here's how Coyne tries to digest it:

If you translate [Fodor and Piattelli-Palmarini's core argument] into layman's English, here's what it says: "Since it's impossible to figure out exactly which changes in organisms occur via direct selection and which are byproducts, natural selection can't operate." Clearly, [they] are confusing our ability to understand how a process operates with whether it operates. It's like saying that because we don't understand how gravity works, things don't fall.

I've read some excerpts of the the book, and it also appears to be laden with eumerdification: writing so dense and jargon-filled it seems to be that way to obscure rather than clarify. I suspect Fodor and Piattelli-Palmarini might have been so clever and convoluted in their writing that they even fooled themselves. That's a pity, because on the face of it, their book might have been a valuable exercise, but instead it looks like a waste of time.

Coyne, by the way, really likes Dawkins's book, probably more than I did. I certainly think it's a more worthwhile and far more comprehensible read.

Labels: books, controversy, darwin, evolution, review, science

18 April 2010

The Fish House, 45 years later

On Saturday, April 17, 1965, my parents were married in St. Andrews Wesley Church on Burrard Street in downtown Vancouver. They held their reception that evening, in a building constructed as the Stanley Park Sports Pavilion in 1930. Today it's the home of the Fish House restaurant.

Last night, 45 years later, also on a Saturday, they returned to the Fish House for an anniversary dinner:

My wife Air, our daughter Marina, and I were happy to join them. (Our younger daughter was at a friend's birthday sleepover.)

I haven't been to the Fish House in at least 15 years, but I won't wait that long again. The food was great—with the added benefit of legacy dishes imported from Vancouver's legendary and recently-closed seaside restaurant, the Cannery. The salmon, prawns, and scallops I ate were excellent, but the rare tuna steak that Air ordered (and which she let me try) was extraordinary.

In August, Air and I will mark 15 years since our wedding in 1995. I hope we can make it to 45, however unlikely my health makes that seem right now. In the meantime, happy anniversary, Mom and Dad. Thanks for inviting us along.

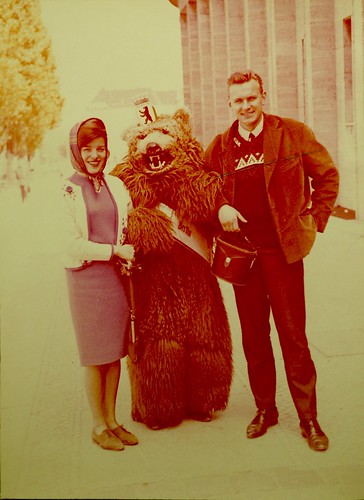

P.S. Here were my parents later in 1965, in Berlin, on their honeymoon:

Labels: anniversary, family, food, restaurant, review, vancouver

21 January 2010

Review: "It Might Get Loud"

If you're a guitar or rock music nerd (like me), you need to see It Might Get Loud. My friend Andrew recommended it to me a few weeks ago, and I was reminded about it on the 37signals blog. The film is a documentary featuring Jimmy Page (of Led Zeppelin), The Edge (of U2), and Jack White (of The White Stripes and The Raconteurs), talking about how they came to be guitarists, playing individually, and jamming together on a faux–sitting-room set built in a warehouse.

So if you're a guitar nerd, you might be off to buy the DVD right now. Still, it's worth knowing why this is not just some self-indulgent guitar wank-fest, and why it's also worthwhile for general music fans too.

No doubt Page, Edge, and White are three of the most influential and popular electric guitarists of the past 40 or 50 years. It would have been interesting to add, say, Tom Morello or Eddie Van Halen to the mix, but I think director Davis Guggenheim was wise to structure the film around a tripod of players—Page from the '60s and '70s, Edge from the '80s and '90s, and White from this past decade.

Each of them talks about individual songs that helped propel them to their current careers. Jimmy Page, resplendent in a long coat and silver hair just the right length for an elder statesman of rock 'n' roll, listens to Link Wray's "Rumble" crackle from a 45 rpm single—he jams along on air guitar and also turns a phantom tremolo knob on an invisible amp to demonstrate how Wray took that classic instrumental to a new level, and grins in sheer joy as he must have as a teenager.

The Edge recalls watching The Jam blast away the twee pop and bland '70s rock that dominated Top of the Pops on British TV in his youth. Jack White puts Son House's skeletal "Grinnin' in Your Face" (just vocals and off-time handclaps) on the turntable and says it's been his favourite song since he first heard it as a kid.

And that's the funny thing. White, who's 34, turned five years old in 1980, the year Led Zeppelin disbanded and U2 released their first album, Boy. For most guitarists of his generation, walking into a room with your guitar to meet Jimmy Page and The Edge would be terrifying, especially when they asked you to teach them one or two of your songs. But in some ways White comes across as the oldest of the group, a pasty-faced ghost from the 1950s or earlier, wrestling with his ravaged and literally thrift-store Kay guitar, wearing a bowtie and a hat and smoking stubby cigars, channeling Blind Willie McTell and Elmore James, building a slide guitar out of some planks, a Coke bottle, and a metal string, assembled with hammer and nails:

While Page and The Edge both grew up in the British Isles, and have never held any jobs besides playing guitar, White is from Detroit, and his hip-hop and house-music–listening cohorts in the '80s and early '90s thought that playing an instrument of any kind was embarrassing, so he didn't come to guitar until he'd already worked as an upholsterer. Somehow, though, if White and Page are rooted in gutbucket, distorted blues, it's still The Edge who seems to be coming from outer space. When he plays his echoing, beautiful intro to "Bad" alone on the soundstage, it's a sound neither of the other players could have created.

During the guitar summit, each of the guitarists teaches the others a couple of his songs. The Edge's first one is "I Will Follow," and it works better than any of the rest, in part because, as he explains, he often creates guitar parts with the absolute minimum of notes, so that they sound clearer, more distinctive, and less muddy when played really loud. And Page and White play really loud. Together the result is, as Jimmy Page says, "roaring."

Labels: band, film, guitar, movie, music, review

17 January 2010

Considering "Avatar"

I'm still not sure quite what I think—on balance—about Avatar, which my wife and I saw last week. In one respect, it's one of very few movies (pretty much all of them fantasy or science fiction) that show you things you've never seen before, and which will inevitably change what other movies look like. It's in the company of The Wizard of Oz, Forbidden Planet, 2001: A Space Odyssey, Star Wars, Blade Runner, Tron, Zelig, Who Framed Roger Rabbit?, Jurassic Park, Babe, Toy Story, The Matrix, and the Lord of the Rings films. It's tremendously entertaining. Anyone who likes seeing movies on a big screen should watch it.

I also don't know if anyone is better at choreographing massive action sequences than Avatar's director, James Cameron—nor of making a three-hour film seem not nearly that long. Maybe, with its massive success, we'll finally see fewer movies with the distinctive cold blue tint and leathery CGI monsters stolen from the Lord of the Rings trilogy. (Maybe in a few years we'll all be tired of lush, phosphorescent Pandora-style forests instead.) Avatar is also the first truly effective use of 3D I've seen in a film: it's not a distraction, not a gimmick, and not overemphasized. It's just part of how the movie was made, and you don't have to think about it, for once.

But a couple of skits on last night's Saturday Night Live, including "James Cameron's Laser Cats 5," in which both James Cameron and Sigourney Weaver appeared, reminded me of some of Avatar's problems:

- Cameron has been thinking about this project since the beginning of his career over three decades ago, and it shows. Or rather, it shows in every other movie he's made. That's because Avatar includes a grab-bag of common Cameron concepts: humanoids that aren't quite what they seem (The Terminator and Terminator 2); kick-ass interstellar marines—including a butch-but-sensitive Latino woman—piloting big walking and flying machines (Aliens); state-of-the-art CGI effects pushed to their limits (The Abyss, Terminator 2, and Titanic); money-grubbing corporate/elite bad guys (Aliens, Titanic), hovering, angular, futuristic transport vehicles (True Lies, The Terminator, The Abyss, Aliens); a love story that turns one of its participants away from societal conventions (Titanic); people traveling to distant planets in suspended animation (Aliens), and of course a lot of stuff that Blows Up Real Good.

- The storyline, despite its excellent execution, is remarkably simplistic, and could easily have been adapted from a mid-tier Disney animation like The Aristocats or Mulan, or (most pointedly) Pocahontas. It's the Noble Savage rendered in blue alien flesh. No doubt much of that is intentional, since some of our most powerful and lasting stories are simple. But I think all the talent and technology behind this movie could have served something more sophisticated, or at least more morally nuanced.

- With all the spectacle of Pandora—the glowing forest plants, the bizarre pulsing and spinning animal life, the floating mountains, the lethal multi-limbed predators—somehow it didn't feel alien enough to me. The most jarring foreign feeling came in the views of Pandora's sky, reminding us that it is not a planet but one of many moons of a looming, ominous gas giant like Jupiter. The humanoid Na'vi, despite all the motion capture that went into translating human actors' performances into new bodies, still seem, in a way, like very, very well-executed rubber suits. The pre-CGI aliens of Aliens (especially the alien queen) were, to me, more convincing despite often actually being people in suits.

- Overall, Avatar isn't James Cameron's best film. I'd choose either Aliens or Terminator 2: Judgment Day as superior. I remember each one leaving me almost speechless. That's because they were exhilarating and—more important—profoundly satisfying, both emotionally and intellectually. Avatar, despite its many riches, didn't satisfy me the same way.

Now, if you're among the 3% of people who haven't seen Avatar yet, I still recommend you do, in a big-screen theatre, in 3D if you can. Like several of the other technically and visually revolutionary movies I listed in my first paragraph (Star Wars and Tron come to mind), its flaws wash away as you watch, consumed and overwhelmed by its imaginary world.

James Cameron apparently plans to make two Avatar sequels. Normally that might dismay me, but his track record of improving upon the original films in a series, whether someone else's or his own (see my last bullet point above), tells me he might be able to pull off something amazing there. Now that he has established Pandora as a place, and had time to develop his new filmmaking techniques, it could be very interesting to see what he does with them next.

Labels: film, movie, review, sciencefiction, space

28 October 2009

Evolution book review: Dawkins's "Greatest Show on Earth," Coyne's "Why Evolution is True," and Shubin's "Your Inner Fish"

Next month, it will be exactly 150 years since Charles Darwin published On the Origin of Species in 1859. This year also marked what would have been his 200th birthday. Unsurprisingly, there are a lot of new books and movies and TV shows and websites about Darwin and his most important book this year.

Next month, it will be exactly 150 years since Charles Darwin published On the Origin of Species in 1859. This year also marked what would have been his 200th birthday. Unsurprisingly, there are a lot of new books and movies and TV shows and websites about Darwin and his most important book this year.

Of the books, I've bought and read the three of the highest-profile ones: Neil Shubin's Your Inner Fish (actually published in 2008), Jerry Coyne's Why Evolution is True, and Richard Dawkins's The Greatest Show on Earth: The Evidence for Evolution. They're all written by working (or, in Dawkins's case, officially retired) evolutionary biologists, but are aimed at a general audience, and tell compelling stories of what we know about the history of life on Earth and our part in it. I also re-read my copy of the first edition of the Origin itself, as well as legendary biologist Ernst Mayr's 2002 What Evolution Is, a few months ago.

Why now?

Aside from the Darwin anniversaries, I wanted to read the three new books because a lot has changed in the study of evolution since I finished my own biology degree in 1990. Or, I should say, not much has changed, but we sure know a lot more than we did even 20 years ago. As with any strong scientific idea, evidence continues accumulating to reinforce and refine it. When I graduated, for instance:

- DNA sequencing was rudimentary and horrifically expensive, and the idea of compiling data on an organism's entire genome was pretty much a fantasy. Now it's almost easy, and scientists are able to compare gene sequences to help determine (or confirm) how different groups of plants and animals are related to each other.

- Our understanding of our relationship with chimpanzees and our extinct mutual relatives (including Australopithecus, Paranthropus, Sahelanthropus, Orrorin, Ardipithecus, Kenyanthropus, and other species of Homo in Africa) was far less developed. With more fossils and more analysis, we know that our ancestors walked upright long before their brains got big, and that raises a host of new and interesting questions.

- The first satellite in the Global Positioning System had just been launched, so it was not yet easily possible to monitor continental drift and other evolution-influencing geological activities happening in real time (though of course it was well accepted from other evidence). Now, whether it's measuring how far the crust shifted during earthquakes or watching as San Francisco marches slowly northward, plate tectonics is as real as watching trees grow.

- Dr. Richard Lenski and his team had just begun what would become a decades-long study of bacteria, which eventually (and beautifully) showed the microorganisms evolving new biochemical pathways in a lab over tens of thousands of generations. That's substantial evolution occurring by natural selection, incontrovertibly, before our eyes.

- In Canada, the crash of Atlantic cod stocks and controversies over salmon farming in the Pacific hadn't yet happened, so the delicate balances of marine ecosystems weren't much in the public eye. Now we understand that human pressures can disrupt even apparently inexhaustible ocean resources, while impelling fish and their parasites to evolve new reproductive and growth strategies in response.

- Antibiotic resistance (where bacteria in the wild evolve ways to prevent drugs from being as effective as they used to) was on few people's intellectual radar, since it didn't start to become a serious problem in hospitals and other healthcare environments until the 1990s. As with cod, we humans have unwittingly created selection pressures on other organisms that work to our own detriment.

...and so on. Perhaps most shocking in hindsight, back in 1990 religious fundamentalism of all stripes seemed to be on the wane in many places around the world. By association, creationism and similar world views that ignore or deny that biological evolution even happens seemed less and less important.

Or maybe it just looked that way to me as I stepped out of the halls of UBC's biology buildings. After all, whether studying behavioural ecology, human medicine, cell physiology, or agriculture, no one there could get anything substantial done without knowledge of evolution and natural selection as the foundations of everything else.

Why these books?

The books by Shubin, Coyne, and Dawkins are not only welcome and useful in 2009, they are necessary. Because unlike in other scientific fields—where even people who don't really understand the nature of electrons or fluid dynamics or organic chemistry still accept that electrical appliances work when you turn them on, still fly in planes and ride ferryboats, and still take synthesized medicines to treat diseases or relieve pain—there are many, many people who don't think evolution is true.

No physicians must write books reiterating that, yes, bacteria and viruses are what spread infectious diseases. No physicists have to re-establish to the public that, honestly, electromagnetism is real. No psychiatrists are compelled to prove that, indeed, chemicals interacting with our brain tissues can alter our senses and emotions. No meteorologists need argue that, really, weather patterns are driven by energy from the Sun. Those things seem obvious and established now. We can move on.

But biologists continue to encounter resistance to the idea that differences in how living organisms survive and reproduce are enough to build all of life's complexity—over hundreds of millions of years, without any pre-existing plan or coordinating intelligence. But that's what happened, and we know it as well as we know anything.

If the Bible or the Qu'ran is your only book, I doubt much will change your mind on that. But many of the rest of those who don't accept evolution by natural selection, or who are simply unsure of it, may have been taught poorly about it back in school—or if not, they might have forgotten the elegant simplicity of the concept. Not to mention the huge truckloads of evidence to support evolutionary theory, which is as overwhelming (if not more so) and more immediate than the also-substantial evidence for our theories about gravity, weather forecasting, germs and disease, quantum mechanics, cognitive psychology, or macroeconomics.

Enjoying the human story

So, if these three biologists have taken on the task of explaining why we know evolution happened, and why natural selection is the best mechanism to explain it, how well do they do the job? Very well, but also differently. The titles tell you.

Shubin's Your Inner Fish is the shortest, the most personal, and the most fun. Dawkins's The Greatest Show on Earth is, well, the showiest, the biggest, and the most wide-ranging. And Coyne's Why Evolution is True is the most straightforward and cohesive argument for evolutionary biology as a whole—if you're going to read just one, it's your best choice.

However, of the three, I think I enjoyed Your Inner Fish the most. Author Neil Shubin was one of the lead researchers in the discovery and analysis of Tiktaalik, a fossil "fishapod" found on Ellesmere Island here in Canada in 2004. It is yet another demonstration of the predictive power of evolutionary theory: knowing that there were lobe-finned fossil fish about 380 million years ago, and obviously four-legged land dwelling amphibian-like vertebrates 15 million years later, Shubin and his colleagues proposed that an intermediate form or forms might exist in rocks of intermediate age.

Ellesmere Island is a long way from most places, but it has surface rocks about 375 million years old, so Shubin and his crew spent a bunch of money to travel there. And sure enough, there they found the fossil of Tiktaalik, with its wrists, neck, and lungs like a land animal, and gills and scales like a fish. (Yes, it had both lungs and gills.) Shubin uses that discovery to take a voyage through the history of vertebrate anatomy, showing how gill slits from fish evolved over tens of millions of years into the tiny bones in our inner ear that let us hear and keep us balanced.

Since we're interested in ourselves, he maintains a focus on how our bodies relate to those of our ancestors, including tracing the evolution of our teeth and sense of smell, even the whole plan of our bodies. He discusses why the way sharks were built hundreds of millions of years ago led to human males getting certain types of hernias today. And he explains why, as a fish paleontologist, he was surprisingly qualified to teach an introductory human anatomy dissection course to a bunch of medical students—because knowing about our "inner fish" tells us a lot about why our bodies are this way.

Telling a bigger tale

Richard Dawkins and Jerry Coyne tell much bigger stories. Where Shubin's book is about how we people are related to other creatures past and present, the other two seek to explain how all living things on Earth relate to each other, to describe the mechanism of how they came to the relationships they have now, and, more pointedly, to refute the claims of people who don't think those first two points are true.

Dawkins best expresses the frustration of scientists with evolution-deniers and their inevitable religious motivations, as you would expect from the world's foremost atheist. He begins The Greatest Show on Earth with a comparison. Imagine, he writes, you were a professor of history specializing in the Roman Empire, but you had to spend a good chunk of your time battling the claims of people who said ancient Rome and the Romans didn't even exist. This despite those pesky giant ruins modern Romans have had to build their roads around, and languages such as Italian, Spanish, Portuguese, French, German, and English that are obviously derived from Latin, not to mention the libraries and museums and countrysides full of further evidence.

He also explains, better than anyone I've ever read, why various ways of determining the ages of very old things work. If you've ever wondered how we know when a fossil is 65 million years old, or 500 million years old, or how carbon dating works, or how amazingly well different dating methods (tree ring information, radioactive decay products, sedimentary rock layers) agree with one another, read his chapter 4 and you'll get it.

Alas, while there's a lot of wonderful information in The Greatest Show on Earth, and many fascinating photos and diagrams, Dawkins could have used some stronger editing. The overall volume comes across as scattershot, assembled more like a good essay collection than a well-planned argument. Dawkins often takes needlessly long asides into interesting but peripheral topics, and his tone wanders.

Sometimes his writing cuts precisely, like a scalpel; other times, his breezy footnotes suggest a doddering old Oxford prof (well, that is where he's been teaching for decades!) telling tales of the old days in black school robes. I often found myself thinking, Okay, okay, now let's get on with it.

Truth to be found

On the other hand, Jerry Coyne strikes the right balance and uses the right structure. On his blog and in public appearances, Coyne is (like Dawkins) a staunch opponent of religion's influence on public policy and education, and of those who treat religion as immune to strong criticism. But that position hardly appears in Why Evolution is True at all, because Coyne wisely thinks it has no reason to. The evidence for evolution by natural selection stands on its own.

I wish Dawkins had done what Coyne does—noting what the six basic claims of current evolutionary theory are, and describing why real-world evidence overwhelmingly shows them all to be true. Here they are:

- Evolution: species of organisms change, and have changed, over time.

- Gradualism: those changes generally happen slowly, taking at least tens of thousands of years.

- Speciation: populations of organisms not only change, but split into new species from time to time.

- Common ancestry: all living things have a single common ancestor—we are all related.

- Natural selection: evolution is driven by random variations in organisms that are then filtered non-randomly by how well they reproduce.

- Non-selective mechanisms: natural selection isn't the only way organisms evolve, but it is the most important.

The rest of Coyne's book, in essence, fleshes those claims and the evidence out. That's almost it, and that's all it needs to be. He recounts too why, while Charles Darwin got all six of them essentially right back in 1859, only the first three or four were generally accepted (even by scientists) right away. It took the better part of a century for it to be obvious that he was correct about natural selection too, and even more time to establish our shared common ancestry with all plants, animals, and microorganisms.

Better than other books about evolution I've read, Why Evolution is True reveals the relentless series of tests that Darwinism has been subjected to, and survived, as new discoveries were made in astronomy, geology, physics, physiology, chemistry, and other fields of science. Coyne keeps pointing out that it didn't have to be that way. Darwin was wrong about quite a few things, but he could have been wrong about many more, and many more important ones.

If inheritance didn't turn out to be genetic, or further fossil finds showed an uncoordinated mix of forms over time (modern mammals and trilobites together, for instance), or no mechanism like plate tectonics explained fossil distributions, or various methods of dating disagreed profoundly, or there were no imperfections in organisms to betray their history—well, evolutionary biology could have hit any number of crisis points. But it didn't.

Darwin knew nothing about some of these lines of evidence, but they support his ideas anyway. We have many more new questions now too, but they rest on the fact of evolution, largely the way Darwin figured out that it works.

The questions and the truth

Facts, like life, survive the onslaughts of time. Opponents of evolution by natural selection have always pointed to gaps in our understanding, to the new questions that keep arising, as "flaws." But they are no such thing: gaps in our knowledge tell us where to look next. Conversely, saying that a god or gods, some supernatural agent, must have made life—because we don't yet know exactly how it happened naturally in every detail—is a way of giving up. It says not only that there are things we don't know, but things we can never learn.

Some of us who see the facts of evolution and natural selection, much the way Darwin first described them, prefer not to believe things, but instead to accept them because of supporting scientific evidence. But I do believe something: that the universe is coherent and comprehensible, and that trying to learn more about it is worth doing for its own sake.

In the 150 years since the Origin, people who believed that—who did not want to give up—have been the ones who helped us learn who we, and the other organisms who share our planet, really are. Thousands of researchers across the globe help us learn that, including Dawkins exploring how genes, and ideas, propagate themselves; Coyne peering at Hawaiian fruit flies through microscopes to see how they differ over generations; and Shubin trekking to the Canadian Arctic on the educated guess that a fishapod fossil might lie there.

The writing of all three authors pulses with that kind of enthusiasm—the urge to learn the truth about life on Earth, over more than 3 billion years of its history. We can admit that we will always be somewhat ignorant, and will probably never know everything. Yet we can delight in knowing there will always be more to learn. Such delight, and the fruits of the search so far, are what make these books all good to read during this important anniversary year.

Labels: anniversary, books, controversy, evolution, religion, review, science

14 September 2009

Book Review: Say Everything

It's a bit weird reading Say Everything, Scott Rosenberg's book about the history of blogging. I've read lots of tech books, but this one involves many people I know, directly or indirectly, and an industry I've been part of since its relatively early days. I've corresponded with many of the book's characters, linked back and forth with them, even met a few in person from time to time. And I directly experienced and participated in many of the changes Rosenberg writes about.

It's a bit weird reading Say Everything, Scott Rosenberg's book about the history of blogging. I've read lots of tech books, but this one involves many people I know, directly or indirectly, and an industry I've been part of since its relatively early days. I've corresponded with many of the book's characters, linked back and forth with them, even met a few in person from time to time. And I directly experienced and participated in many of the changes Rosenberg writes about.

The history the book tells, mostly in the first couple of hundred pages, feels right. He doesn't try to find The First Blogger, but he outlines how the threads came together to create the first blogs, and where things went after that. Then Rosenberg turns to analysis and commentary, which is also good. I never found myself thinking, Hey, that's not right! or You forgot the most important part!—and according to Rosenberg, that was the feeling about mainstream reporting that got people like Dave Winer blogging to begin with.

Rosenberg's last book came out only last year, in 2008, so much of what's in Say Everything is remarkably current. He covers why blogging is likely to survive newer phenomena like Facebook and Twitter. And he doesn't hold back in his scorn for the largely old-fashioned thinking of his former newspaper colleagues (he used to work at the San Francisco Examiner before helping found Salon).

But then I hit page 317, where he writes:

...bloggers attend to philosophical discourse as well as pop-cultural ephemera; they document private traumas as well as public controversies. They have sought faith and spurned it, chronicled awful illnesses and mourned unimaginable losses. [My emphasis - D.]

That caused a bit of a pang. After all, that's what I've been doing here for the past few years. It hit close to home. Next, page 357:

For some wide population of bloggers, there is ample reason to keep writing about a troubled marriage or a cancer diagnosis or a death in the family, regardless of how many ethical dilemmas must be traversed, or how trivial or amateurish their labours are judged. [Again, my emphasis - D.]

Okay, sure, there are lots of cancer bloggers out there. I'm just projecting my own experience onto Rosenberg's writing, right? Except, several hundred pages earlier, Rosenberg had written about an infamous blogger dustup between Jason Calacanis and Dave Winer at the Gnomedex 2007 conference in Seattle.

The same conference where, via video link, I gave a presentation, about which Rosenberg wrote on his blog:

Derek K. Miller is a longtime Canadian blogger [who'd] been slated to give a talk at Gnomedex, but he’s still recovering from an operation, so making the trip to Seattle wasn’t in the cards. Instead, he spoke to the conference from his bed via a video link, and talked about what it’s been like to tell the story of his cancer experience in public and in real time. Despite the usual video-conferencing hiccups (a few stuttering images and such), it was an electrifying talk.

Later that month, he mentioned me in an article in the U.K.'s Guardian newspaper. When he refers to people blogging about a cancer diagnosis, he doesn't just mean people like me, he means me. Thus I don't think I can be objective about this book. I think it's a good one. I think it tells an honest and comprehensive story about where blogging came from and why it's important. Yet I'm too close to the story—even if not by name, I'm in the story—to evaluate it dispassionately.

Then again, as Rosenberg writes, one of blogging's strengths is in not being objective. In declaring your interests and conflicts and forging ahead with your opinion and analysis anyway, and interacting online with other people who have other opinions.

So, then: Say Everything is a good book. You should read it—after all, not only does it talk about a lot of people I know, I'm in it too!

Labels: blog, books, cancer, gnomedex, history, review, web

04 June 2009

The digital decline of Annie Leibovitz's photography

Bad Astronomer Phil Plait likes the photography of Annie Leibovitz, such as this ad photo for Louis Vuitton bags featuring astronauts Sally Ride, Buzz Aldrin, and Jim Lovell. Despite her fame and the excellent work she's done in the past, I find most of Leibovitz's current work aesthetically repulsive.

Bad Astronomer Phil Plait likes the photography of Annie Leibovitz, such as this ad photo for Louis Vuitton bags featuring astronauts Sally Ride, Buzz Aldrin, and Jim Lovell. Despite her fame and the excellent work she's done in the past, I find most of Leibovitz's current work aesthetically repulsive.

A bit of a rant here. Annie used to take good photos, and she still occasionally does, but her advertising work (including this picture) and many of her portraits long ago strayed much too far into over-Photoshopped territory. One critic even called a picture she created last year the worst photograph ever made, and I'm inclined to agree.

I think this would have been a much better photo with the same people, all of whom I admire, plus the same truck and the same bag, outside on a sunny day, maybe on the landing strip at Edwards Air Force Base. Maybe in black and white. The example here is overlit, over-processed, oversaturated, and ingenuine. Their facial expressions aren't that great. And yeah, if they're supposed to be looking at and lit by the Moon, it's in entirely the wrong place in the image. Even a non-nerd can probably detect that intuitively.

Compare her classic portrait of Whoopi Goldberg in the bath (11th down on this page) to her recent Photoshop monstrosity of Whoopi (second down on this page).

I admire surreal photography and well-executed photo manipulation, whether using Photoshop or high-dynamic-range (HDR) imaging. But Leibovitz isn't doing that. She and her team of assistants have manipulated the life out of her images. Much of her new stuff reminds me of velvet paintings of dogs playing poker. The astronaut ad is no exception.

Labels: controversy, photography, review, software

09 May 2009

Redeeming the prequel

Remember back in 2006 when I raved about the then-new Casino Royale? It defined how to reboot a movie franchise. And the new Star Trek, which I saw tonight, learned that James Bond lesson, in spades.

Remember back in 2006 when I raved about the then-new Casino Royale? It defined how to reboot a movie franchise. And the new Star Trek, which I saw tonight, learned that James Bond lesson, in spades.

Trek never shied away from time travel—the old crew used it to do everything from keeping the Nazis from winning the War to saving the whales (and the Earth). But the new movie is especially clever with it, managing to maintain the integrity of the original series and movies, and all their sequels, while giving the "new" crew entirely different directions to go.

In another way, that hardly matters. My kids enjoyed the movie tremendously, even though they know basically nothing about previous Treks. It's just a great big ball of fun. Despite all the praise it's received, it was also still considerably better than I expected.

But that was Winona Ryder? Didn't even recognize her.

Labels: film, movie, review, startrek

10 April 2009

My review of GarageBand '09

Over the past year, I've put myself forward as something of an expert on GarageBand, Apple's intro-level audio recording and podcasting application. I've been using the program intensively, through every version upgrade, since it first appeared in 2004, and I've kept in touch with Apple (through both formal and informal channels) about it ever since.

Over the past year, I've put myself forward as something of an expert on GarageBand, Apple's intro-level audio recording and podcasting application. I've been using the program intensively, through every version upgrade, since it first appeared in 2004, and I've kept in touch with Apple (through both formal and informal channels) about it ever since.

Plus you can now buy a comprehensive video course I recorded to show you how GarageBand works.

So you might wonder what I think of Apple's newest version of the program. If so, I've just published a big GarageBand '09 review article over at the Inside Home Recording blog, which should interest you. There's also a link to my audio review from a couple of weeks ago.

Labels: apple, education, insidehomerecording, music, podcast, recording, review, software

05 February 2009

The big gap

For the past couple of weeks I've been reading God's Crucible

For the past couple of weeks I've been reading God's Crucible, a history book by David Levering Lewis—which I gave to my dad for Christmas, but which he's loaned back to me. Today I got a lot of reading done, because my body was screwing with me: I'll have to skip my cancer medications for the next day or two because the intestinal side effects, unusually, lasted all day today and into the night, and I have to give my digestive system (and my butt) a rest.

Lewis's book covers, at its core, a 650-year span from the 500s to the 1200s, during which Islam began, and rapidly spread the influence of its caliphate from Arabia across a big swath of Eurasia and northern Africa, while what had been the Roman Empire simultaneously fragmented into its Middle Ages in Europe. That's a time I've known little about until now.

The history I took in school and at university covered lots of things, from ancient Egypt and Babylon up to the Roman Empire, and from the Renaissance to the 20th century, as well as medieval England. I learned something about the history of China and India, as well as about the pre-Columbian Americas. But pre-Renaissance Europe and the simultaneous rapid expansion of the dar al-Islam are a particularly big gap for me.

Whose Dark Ages?

I knew a little about Moorish Spain, and a tad about Charlemagne and Constantinople, but otherwise it was just the Dark Ages for me, and for a lot of students who learned the typical Eurocentric view of history. There was much more going on in more populated and interesting parts of the world, though. While Europeans (not even yet named that) eked along with essentially no currency, trade, or much cultural exchange beyond warfare with horses, swords, and arrows:

- China went through the Sui, Tang, and Song dynasties, reaching the peak of classical Chinese art, culture, and technology.

- India also saw several dynasties and empires, as well as its own Muslim sultans.

- Large kingdoms of the Sahel in near-equatorial Africa arose, including those of Ghana, Takrur, Malinke, and Songhai.

- The Maya in Central America developed city-states and the only detailed written language in the Western Hemisphere.

- The seafaring Polynesians reached their most distant Pacific outposts, including Easter Island, Hawaii, and New Zealand.

Crucially important, of course, was Islam. Muhammad was born in the year 570, and shortly after he died about six decades later, Muslim armies exploded out of Arabia and conquered much of the Middle East and North Africa, then expanded east and north into Central Asia. By the early 700s, the influence of the caliphate headquartered in Damascus had reached Spain (al-Andalus), where Muslims would remain in power for 700 years.

In his book, Lewis flies through the origins of Islam, the foundations of the Byzantine and Roman branches of the Catholic Church after the fall of Rome, the interminable conflict between it and Zoroastrian Persia to the east, the Muslim caliphate's sudden rise up the middle to take over the eastern and southern Mediterranean, and the crossing of Islamic armies into Europe at Jebel Tariq (now called Gibraltar) in 711. Then things bog down a little.

I'm about half-way through the book, and Lewis throws out so many names, alternate names for the same people, events, places, and such that it's hard to keep up. He hops back and forth in time enough that what story he's trying to tell isn't always clear—he was won the Pulitzer Prize, but that was for more focused historical biographies, such as of W.E.B. Du Bois, rather than sweeping surveys like this one. His writing isn't overly complex, and I'm learning a lot, but it's a tough go sometimes. Still, I think it will be worth sticking it out.

Labels: books, europe, history, religion, review

04 February 2009

iLife '09 is worth the upgrade

If you have a Mac, Apple's $100 Cdn iLife suite of programs is perhaps the best deal in software today. That may be true even if you don't have a Mac, because if you buy one, iLife comes along free—and just a few years ago, the features of any one of its programs would have cost you more than the computer does today. So depending on what you do, it's almost like you're getting the Mac for free instead.

If you have a Mac, Apple's $100 Cdn iLife suite of programs is perhaps the best deal in software today. That may be true even if you don't have a Mac, because if you buy one, iLife comes along free—and just a few years ago, the features of any one of its programs would have cost you more than the computer does today. So depending on what you do, it's almost like you're getting the Mac for free instead.

When it first appeared in 2004, for instance, GarageBand inspired me to start recording music again after a long hiatus. iPhoto is an extremely capable photo cataloguing program, and even as a pretty keen photography enthusiast, it's what I use to manage my collection. For me, iMovie, iWeb, and iDVD come along as bonuses.

iDVD is capable enough on the rare occasions I need to make a video DVD. The new versions of iMovie are still pretty weird, in my book, but they work, and I may warm to the new iMovie '09 now that it's improved over the confusing reboot that was iMovie '08. iWeb—well, as a web guy, it's never been my cup of tea, and I gave up on it a few months ago after giving it a good two-year chance to justify its existence. But some people might like it.

iLife '09 is the latest iteration of the package, and I picked it up last week, shortly after it became available in stores. I'll be reviewing the new GarageBand for Inside Home Recording sometime soon, but there are already some other impressions on the web. Jim Dalrymple at Macworld looks at the new guitar-focused changes in GarageBand, Rick LePage examines iPhoto's new emphasis on face recognition and location awareness, and screenwriter John August takes a crack at iMovie '09.

I have to agree with Fraser Speirs that iPhoto's new integration with Facebook and Flickr looks way too heavy-handed. I actually don't want photos, tags, names, and such synchronized between my computer and those sharing sites. Usually, I just want to push photos out from iPhoto, and maybe make changes on the Web, but I don't want those changes propagating back and forth. I often prefer to collect very different sets in the two places, and may need to name people on my computer but not online, for instance. So I don't think I'll be turning those features on, but will use my old methods instead.

In iLife '09, GarageBand makes big changes, especially in new features (like Lessons) that i didn't even know I'd want, while still keeping what makes it great. iPhoto adds extremely cool new stuff that I'll definitely use, and some other stuff I definitely won't. iMovie may have redeemed itself enough that I'll work with it again. iDVD? We'll, it's still there. And iWeb? Despite good progress, it's just not the way I work with websites (I create almost everything in a text editor).

I'm happy with what I've seen from iLife '09 so far. For $100, as always, it's a total steal.

Labels: apple, music, photography, review, software, video

15 November 2008

Still a sexy beast, if a little addled

The iconic James Bond "shoot at the camera" montage doesn't appear until the end of Quantum of Solace, and that's a good summation of the whole movie: it's fun, but things aren't quite in the right place. In fact, by the time it's over, it seems a bit like a Bond movie trailer that lasts almost two hours.

The iconic James Bond "shoot at the camera" montage doesn't appear until the end of Quantum of Solace, and that's a good summation of the whole movie: it's fun, but things aren't quite in the right place. In fact, by the time it's over, it seems a bit like a Bond movie trailer that lasts almost two hours.

A couple of years ago I raved about Casino Royale, Daniel Craig's first Bond appearance. Quantum isn't as good. It strays too far into Jason Bourne land, where the fights are all dizzying intercuts, the scenes flit around the world almost randomly (Italy, Britain, Haiti, Austria, Bolivia, Russia...), and the various secondary players are so corrupt that there's nearly no one left to root for. There's something emotional missing, and by the time it's over you wonder a little what most of the movie had to do with Bond's end goal.

I'm not saying I didn't like the film. Craig remains extraordinary in the role, steely and taut. There's a lot of clever editing, implying what happens rather than showing it. The action scenes—including chases on foot, in boats, in cars, and on aircraft—spark with energy, even if they occasionally confuse. By the end, you know more about why Bond is who he is, and there's a nice little joke about Canadians, presumably by Canadian lead writer Paul Haggis. Overall, my wife and I enjoyed it.

But next time, the filmmakers need to go back to Casino Royale and figure out why that movie didn't just spark, but was refreshingly, blazingly on fire. They have a good thing going, but they've got to keep it going.

Labels: jamesbond, movie, review

24 September 2008

The return of AC/DC

Holy crap. The recording for AC/DC's new song, "Rock 'n' Roll Train," and the accompanying video, could have been made anytime in the past 30 years. That's what's so awesome about it:

When AC/DC are on, as they appear to be on this new single, it seems they can still take any other rock band you can name and kick its ass around the block. Angus and Malcolm Young have once more constructed guitar riffs massive enough to be hewn from a cliffside. The rhythm resurrects the band's trademark fist-pumping stomp, and the chorus is a gang-vocal sing-along in the great AC/DC tradition. The lyrics are essentially meaningless, as they should be.

Most remarkably, singer Brian Johnson has somehow lost the Donald Duck shriek he developed about 20 years ago, and he's singing better than ever, gritty and soulful and muscular. All in all, it sounds like 1980 all over again. Gloriously. As The Guardian puts it, "Not clever but, oh lordy, it's big." How the hell did this bunch of old dudes do that?

I've already listened to "Rock 'n' Roll Train" half a dozen times since I discovered it tonight. As a musician, I'd be happy if I could create just one brainless rocking genius song like it, ever. The album it comes from is called Black Ice, and will be out in a few weeks.

Labels: band, guitar, music, review

18 August 2008

Photo gearheaddery from Sigma, Canon, and DPReview

Photo buffs (yeah, like me) will be interested to read two new gear reviews at DPReview today:

Photo buffs (yeah, like me) will be interested to read two new gear reviews at DPReview today:

- Sigma's new 50 mm f/1.4 lens is unusual: the first genuinely modern 50 mm lens design in a long time, not from one of the camera manufacturers, and both huge and expensive compared to lenses made by Canon, Nikon, and Pentax (whose comparable lens is half the weight and price!).

- Canon's $8000 EOS 1Ds Mark III is the top of the heap for price and resolution among digital SLR cameras. It's taken awhile for DPR to review it, but it's interesting to see how it compares to Nikon's very different top model, the D3.

Labels: canon, nikon, photography, review, sigma

10 August 2008

When did dark become bleak?

Remember when the Michael Keaton Batman was considered "dark and edgy?" Today, I couldn't even write that without the ironic quotation marks, and without laughing, a bit like the Joker. Because The Dark Knight, that's dark.

These must be dark times, at least for some of us, because even the dark movies are darker. Or not that, really. They are dark, but also bleak. Look at No Country for Old Men, or some earlier films of the same ilk. Alien3 and Leaving Las Vegas come to mind. I left them as I left The Dark Knight, impressed but a bit deflated. I needed a recharge after each one. Which characters don't lose in those movies?

That's not to say there wasn't much to like about The Dark Knight. Heath Ledger, as everyone's been saying, made the definitive Joker. Minutes into his performance, you know that every other version, whether in the comic books or in the hands of Jack Nicholson, only hinted at what the character was really about, and they're all forgotten. Insane and focused, yet unhinged and random, Ledger's is the real fearsome face we'd all dread if he haunted our city.

His Joker is one of the greatest of all movie villains, and yes, I'd still say that if the actor were alive. Right up there with Dracula, Hannibal Lecter, Darth Vader, HAL, Norman Bates, and Nurse Ratched.

But his Joker also dismantles the universe that the other characters live in. Batman included. Right and wrong, good choices and bad—no one knows what's what anymore. And not just inside the movie, but for me in the audience too. This Joker is so dastardly, so industrious, so fiendish, so insidious, that everything the good guys try near the end is fruitless, even when they "win." Again, Batman included. And you know, I'm not sure that's what I go to superhero movies for.

There was another extraordinary performance in a comic book movie this year: Robert Downey Jr. in Iron Man. Downey made that movie, and owned it, and it was fun. I wanted more, right away. In The Dark Knight, Ledger owns the movie too, as he deserves to, because his Joker steals it. How appropriate. But somehow, he steals it from us in the audience as well. Then he unmakes it.

Would I have watched more of Ledger's Joker if he had lived to play him in another Batman sequel? Yes, I think I would. He was mesmerizing. But that won't happen, and the Batman he and director Christopher Nolan have left behind is so hollowed out I'm not sure I want to see more of him. I wonder whether that feeling will linger in a few years when the next sequel arrives, Jokerless.

Labels: film, linkbait, movie, review